Inhabited Landscapes

People in the region of Sudan have been reorganising nature to better suit their needs since time immemorial. Their relationships with nature have evolved over a very long period. Landscapes change and they have been lost due to conflict and climate change, as well as poor stewardship. This topic explores different approaches to reorganising nature.

Mapping Connections

Mapping Connections

Mapping Connections: People, Place, and Heritage

Mapping is a powerful tool for uncovering connections between people, place, and heritage. The creation of heritage base maps highlights how these visual records serve as living reflections of stories, identities, and shared heritage. This collection of five maps offers unique insights into Sudan and the broader Sahel region, illustrating how geography shapes human experiences.

- People and Railways examines the link between population density and the railway infrastructure in Sudan. The design combines geographic, infrastructural, and demographic data to analyze human settlement patterns in relation to transportation infrastructure.

- People and Livelihoods illustrates the diverse livelihood patterns across Sudan, highlighting how different regions rely on various forms of agriculture, pastoralism, and mixed land use. The map also includes, administrative boundaries, and Sahel ecological zones, by visualizing these patterns, the map provides insight into how geography influences economic survival strategies in the region.

- Music and Festivals celebrates the rich cultural landscape of Sudan by mapping musical traditions and festivals across different regions. This visualization provides insight into Sudan's diverse musical expressions and communal celebrations, reflecting its deep-rooted traditions and regional identities.

- The Sahel and Movement provides a detailed representation of migration patterns, biomes, and hydrology across the Sahel region of Africa. It highlights key Sahel zones, while also mapping transborder passage points, trade routes, and nomadic transhumance paths. The map incorporates biomes, such as deserts, savannas, and tropical forests, as well as stream networks and precipitation trends, demonstrating the environmental factors influencing movement. This visualization offers insight into how geography, climate, and human mobility interact in one of the most dynamic regions of Africa.

- People and the Nile illustrates the relationship between human settlements and the Nile River. It highlights populated areas, with a clear concentration of settlements along the Nile and its tributaries, emphasizing the river's crucial role in supporting life. The map also depicts hydrological features, including stream networks, and the Nile Basin, showcasing the interconnectedness of water systems and human habitation in this arid landscape.

Together, these maps provide a deeper understanding of the intricate relationships between geography, society, and heritage.

Mapping Connections: People, Place, and Heritage

Mapping is a powerful tool for uncovering connections between people, place, and heritage. The creation of heritage base maps highlights how these visual records serve as living reflections of stories, identities, and shared heritage. This collection of five maps offers unique insights into Sudan and the broader Sahel region, illustrating how geography shapes human experiences.

- People and Railways examines the link between population density and the railway infrastructure in Sudan. The design combines geographic, infrastructural, and demographic data to analyze human settlement patterns in relation to transportation infrastructure.

- People and Livelihoods illustrates the diverse livelihood patterns across Sudan, highlighting how different regions rely on various forms of agriculture, pastoralism, and mixed land use. The map also includes, administrative boundaries, and Sahel ecological zones, by visualizing these patterns, the map provides insight into how geography influences economic survival strategies in the region.

- Music and Festivals celebrates the rich cultural landscape of Sudan by mapping musical traditions and festivals across different regions. This visualization provides insight into Sudan's diverse musical expressions and communal celebrations, reflecting its deep-rooted traditions and regional identities.

- The Sahel and Movement provides a detailed representation of migration patterns, biomes, and hydrology across the Sahel region of Africa. It highlights key Sahel zones, while also mapping transborder passage points, trade routes, and nomadic transhumance paths. The map incorporates biomes, such as deserts, savannas, and tropical forests, as well as stream networks and precipitation trends, demonstrating the environmental factors influencing movement. This visualization offers insight into how geography, climate, and human mobility interact in one of the most dynamic regions of Africa.

- People and the Nile illustrates the relationship between human settlements and the Nile River. It highlights populated areas, with a clear concentration of settlements along the Nile and its tributaries, emphasizing the river's crucial role in supporting life. The map also depicts hydrological features, including stream networks, and the Nile Basin, showcasing the interconnectedness of water systems and human habitation in this arid landscape.

Together, these maps provide a deeper understanding of the intricate relationships between geography, society, and heritage.

Mapping Connections: People, Place, and Heritage

Mapping is a powerful tool for uncovering connections between people, place, and heritage. The creation of heritage base maps highlights how these visual records serve as living reflections of stories, identities, and shared heritage. This collection of five maps offers unique insights into Sudan and the broader Sahel region, illustrating how geography shapes human experiences.

- People and Railways examines the link between population density and the railway infrastructure in Sudan. The design combines geographic, infrastructural, and demographic data to analyze human settlement patterns in relation to transportation infrastructure.

- People and Livelihoods illustrates the diverse livelihood patterns across Sudan, highlighting how different regions rely on various forms of agriculture, pastoralism, and mixed land use. The map also includes, administrative boundaries, and Sahel ecological zones, by visualizing these patterns, the map provides insight into how geography influences economic survival strategies in the region.

- Music and Festivals celebrates the rich cultural landscape of Sudan by mapping musical traditions and festivals across different regions. This visualization provides insight into Sudan's diverse musical expressions and communal celebrations, reflecting its deep-rooted traditions and regional identities.

- The Sahel and Movement provides a detailed representation of migration patterns, biomes, and hydrology across the Sahel region of Africa. It highlights key Sahel zones, while also mapping transborder passage points, trade routes, and nomadic transhumance paths. The map incorporates biomes, such as deserts, savannas, and tropical forests, as well as stream networks and precipitation trends, demonstrating the environmental factors influencing movement. This visualization offers insight into how geography, climate, and human mobility interact in one of the most dynamic regions of Africa.

- People and the Nile illustrates the relationship between human settlements and the Nile River. It highlights populated areas, with a clear concentration of settlements along the Nile and its tributaries, emphasizing the river's crucial role in supporting life. The map also depicts hydrological features, including stream networks, and the Nile Basin, showcasing the interconnectedness of water systems and human habitation in this arid landscape.

Together, these maps provide a deeper understanding of the intricate relationships between geography, society, and heritage.

The Jubraka agricultural model

The Jubraka agricultural model

The Jubraka (plural Jabarik) in western Sudan is one of the traditional agricultural practices that form an essential part of the lives of many rural communities in the region. It is a model of household, or small-scale farming, that relies on small plots of land surrounding homes or within villages, where families grow a variety of crops to meet their food needs and support the local economy. The word Jubraka refers to small agricultural plots, where various crops such as sorghum, millet, sesame, and peanuts are cultivated, along with a variety of vegetables. The people of western Sudan, especially in regions like Darfur and Kordofan, depend on the Jubraka as one of the primary sources of food.

Women play a central role in this form of agriculture, as they are responsible for most of the work, from preparing the land and planting, to harvesting which is why the household agricultural economy in western Sudan largely depends on their efforts. Women’s work on the Jubraka is carried out while they are balancing other responsibilities within the household. This type of agricultural activities enhance the social standing of women by providing them with the ability to contribute to the food security of both the family and the local community. Moreover, the Jubraka offers women an opportunity to improve their living standards by selling surplus crops in local markets, which supports family income and enhances women's economic independence. This important role that women play not only strengthens their social status but also helps improve the level of education and healthcare within their families.

The crops grown in the Jubraka are diverse and include grains like sorghum and millet, which are the main food staples for the local population. Oilseed crops such as sesame and peanuts are also cultivated, providing essential natural oils and proteins. In addition to these, vegetables like okra, tomatoes, onions, cucumbers and salad leaves are grown, adding variety to the diet and helping to improve nutrition. Moreover, the Jubraka is tied to the social and cultural values of western Sudan, representing a part of the cultural identity of local communities. The agriculture practiced in the Jubraka not only provides food but also strengthens social bonds through cooperation among family and community members in various farming activities.

Despite the significant importance of the Jubraka in western Sudan, this traditional form of agriculture has, over the years, faced numerous challenges. One of the most prominent problems is climate change, which negatively affects rainfall patterns and crop yields, leading to food shortages and increased poverty in rural areas. Additionally, the Jubraka suffers from a lack of agricultural resources such as tools and fertilizers, which limits its productivity. Previous armed conflicts in western Sudan, such as those witnessed in Darfur, have resulted in the displacement of many people and the destruction of agricultural lands, directly impacting the sustainability and continuity of Jubraka farming.

Nevertheless, this traditional economic system that relies on manual labour and utilizes available natural resources, helps ensure food security for local populations and reduces their dependence on external markets or food aid. During times of crisis, such as droughts or conflicts, the Jubraka plays a critical role in meeting the minimum food needs of families and communities. Today, and in light of the devastating ongoing war, the Jubraka model of growing vegetables and grains is being adopted across Sudan wherever land and water are available. Sudanese people on social media have shared images of their gardens, courtyards and empty plots of land being tilled in preparation to being used for agriculture. Pictures of the vegetables that have been harvested are proudly displayed representing small acts of resilience in the face of food shortages and the rocketing cost of basic commodities.

Header picture: Peanut cultivation – the beginning of the fall season and preparation for it by farmers, Alnuzul Village, White Nile state © Alfadil Hamid

Gallery pictures: Jubraka in El-Obaid, North Kordofan 2024 © Amani Basheer

The Jubraka (plural Jabarik) in western Sudan is one of the traditional agricultural practices that form an essential part of the lives of many rural communities in the region. It is a model of household, or small-scale farming, that relies on small plots of land surrounding homes or within villages, where families grow a variety of crops to meet their food needs and support the local economy. The word Jubraka refers to small agricultural plots, where various crops such as sorghum, millet, sesame, and peanuts are cultivated, along with a variety of vegetables. The people of western Sudan, especially in regions like Darfur and Kordofan, depend on the Jubraka as one of the primary sources of food.

Women play a central role in this form of agriculture, as they are responsible for most of the work, from preparing the land and planting, to harvesting which is why the household agricultural economy in western Sudan largely depends on their efforts. Women’s work on the Jubraka is carried out while they are balancing other responsibilities within the household. This type of agricultural activities enhance the social standing of women by providing them with the ability to contribute to the food security of both the family and the local community. Moreover, the Jubraka offers women an opportunity to improve their living standards by selling surplus crops in local markets, which supports family income and enhances women's economic independence. This important role that women play not only strengthens their social status but also helps improve the level of education and healthcare within their families.

The crops grown in the Jubraka are diverse and include grains like sorghum and millet, which are the main food staples for the local population. Oilseed crops such as sesame and peanuts are also cultivated, providing essential natural oils and proteins. In addition to these, vegetables like okra, tomatoes, onions, cucumbers and salad leaves are grown, adding variety to the diet and helping to improve nutrition. Moreover, the Jubraka is tied to the social and cultural values of western Sudan, representing a part of the cultural identity of local communities. The agriculture practiced in the Jubraka not only provides food but also strengthens social bonds through cooperation among family and community members in various farming activities.

Despite the significant importance of the Jubraka in western Sudan, this traditional form of agriculture has, over the years, faced numerous challenges. One of the most prominent problems is climate change, which negatively affects rainfall patterns and crop yields, leading to food shortages and increased poverty in rural areas. Additionally, the Jubraka suffers from a lack of agricultural resources such as tools and fertilizers, which limits its productivity. Previous armed conflicts in western Sudan, such as those witnessed in Darfur, have resulted in the displacement of many people and the destruction of agricultural lands, directly impacting the sustainability and continuity of Jubraka farming.

Nevertheless, this traditional economic system that relies on manual labour and utilizes available natural resources, helps ensure food security for local populations and reduces their dependence on external markets or food aid. During times of crisis, such as droughts or conflicts, the Jubraka plays a critical role in meeting the minimum food needs of families and communities. Today, and in light of the devastating ongoing war, the Jubraka model of growing vegetables and grains is being adopted across Sudan wherever land and water are available. Sudanese people on social media have shared images of their gardens, courtyards and empty plots of land being tilled in preparation to being used for agriculture. Pictures of the vegetables that have been harvested are proudly displayed representing small acts of resilience in the face of food shortages and the rocketing cost of basic commodities.

Header picture: Peanut cultivation – the beginning of the fall season and preparation for it by farmers, Alnuzul Village, White Nile state © Alfadil Hamid

Gallery pictures: Jubraka in El-Obaid, North Kordofan 2024 © Amani Basheer

The Jubraka (plural Jabarik) in western Sudan is one of the traditional agricultural practices that form an essential part of the lives of many rural communities in the region. It is a model of household, or small-scale farming, that relies on small plots of land surrounding homes or within villages, where families grow a variety of crops to meet their food needs and support the local economy. The word Jubraka refers to small agricultural plots, where various crops such as sorghum, millet, sesame, and peanuts are cultivated, along with a variety of vegetables. The people of western Sudan, especially in regions like Darfur and Kordofan, depend on the Jubraka as one of the primary sources of food.

Women play a central role in this form of agriculture, as they are responsible for most of the work, from preparing the land and planting, to harvesting which is why the household agricultural economy in western Sudan largely depends on their efforts. Women’s work on the Jubraka is carried out while they are balancing other responsibilities within the household. This type of agricultural activities enhance the social standing of women by providing them with the ability to contribute to the food security of both the family and the local community. Moreover, the Jubraka offers women an opportunity to improve their living standards by selling surplus crops in local markets, which supports family income and enhances women's economic independence. This important role that women play not only strengthens their social status but also helps improve the level of education and healthcare within their families.

The crops grown in the Jubraka are diverse and include grains like sorghum and millet, which are the main food staples for the local population. Oilseed crops such as sesame and peanuts are also cultivated, providing essential natural oils and proteins. In addition to these, vegetables like okra, tomatoes, onions, cucumbers and salad leaves are grown, adding variety to the diet and helping to improve nutrition. Moreover, the Jubraka is tied to the social and cultural values of western Sudan, representing a part of the cultural identity of local communities. The agriculture practiced in the Jubraka not only provides food but also strengthens social bonds through cooperation among family and community members in various farming activities.

Despite the significant importance of the Jubraka in western Sudan, this traditional form of agriculture has, over the years, faced numerous challenges. One of the most prominent problems is climate change, which negatively affects rainfall patterns and crop yields, leading to food shortages and increased poverty in rural areas. Additionally, the Jubraka suffers from a lack of agricultural resources such as tools and fertilizers, which limits its productivity. Previous armed conflicts in western Sudan, such as those witnessed in Darfur, have resulted in the displacement of many people and the destruction of agricultural lands, directly impacting the sustainability and continuity of Jubraka farming.

Nevertheless, this traditional economic system that relies on manual labour and utilizes available natural resources, helps ensure food security for local populations and reduces their dependence on external markets or food aid. During times of crisis, such as droughts or conflicts, the Jubraka plays a critical role in meeting the minimum food needs of families and communities. Today, and in light of the devastating ongoing war, the Jubraka model of growing vegetables and grains is being adopted across Sudan wherever land and water are available. Sudanese people on social media have shared images of their gardens, courtyards and empty plots of land being tilled in preparation to being used for agriculture. Pictures of the vegetables that have been harvested are proudly displayed representing small acts of resilience in the face of food shortages and the rocketing cost of basic commodities.

Header picture: Peanut cultivation – the beginning of the fall season and preparation for it by farmers, Alnuzul Village, White Nile state © Alfadil Hamid

Gallery pictures: Jubraka in El-Obaid, North Kordofan 2024 © Amani Basheer

Climate Change and Conflict

Climate Change and Conflict

Today, traditional leaders play important roles in environmental conservation. They enforce local customs that protect the environment, implement statutory laws to safeguard natural resources such as forests and rangelands, and plan areas for farming, animal corridors, and fire guards. However, competition for resources has escalated in recent years. Traditional mechanisms that once existed to resolve conflicts—such as intermarriages between neighbouring tribal groups to promote peaceful coexistence—have become strained. Additionally, Sudan’s population is increasingly young and urbanized. One area of public life where women have been deeply engaged, albeit with little official recognition, is in promoting peace at both national and community levels.

Climate change and prolonged conflict exert almost identical impacts on the environment. Both degrade or deplete natural resources, which in turn affects people’s livelihoods and ability to survive. Poverty and the environment are inextricably linked—human deprivation and environmental degradation reinforce each other. Environmental issues are further exacerbated by inadequate urban planning and a lack of safety regulations for businesses and industries, leading to pollution and environmental degradation.

Sudan's cultural heritage is under threat from multiple forces, including climate change. Across the world, climate change and global warming are making traditional ways of life increasingly uncertain. Material culture, intangible practices, traditional knowledge, and cultural landscapes play a vital role in helping communities adapt to extreme and unpredictable climates. However, these rich traditions are themselves threatened by the unprecedented challenges of climate change. Museums serve as institutions where heritage is preserved for future generations, and they have a role in helping communities understand the impacts of climate change and appreciate the value of their cultural traditions for climate adaptation.

Environmental education is not yet fully integrated into Sudan’s formal education system, except at the basic education level. In 2022, the Western Sudan Community Museums project, as part of efforts to protect Sudanese heritage, developed the Green Heritage Programme with funding from the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund. This initiative raised awareness about the effects of climate change on communities in Sudan and its impact on both tangible and intangible heritage. The programme included a series of workshops in all three museums, a study on the impact of climate change on the intangible culture of nomads in Kordofan, and a major survey of Darfur’s monuments to assess climate change’s effects on the region’s heritage. Conducted by the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), the Afro-Asian Institute at the the University of Khartoum and the University of Nyala’s Darfur Heritage Department, the survey covered 180km and documented 12 major heritage sites in the Furnung, Tagabo, and Meidob Hills.

The project culminated in community exhibitions held at all three museums, providing spaces where diverse communities could come together to celebrate, enjoy, and learn from their unique and shared traditions—both today and for future generations.

Today, traditional leaders play important roles in environmental conservation. They enforce local customs that protect the environment, implement statutory laws to safeguard natural resources such as forests and rangelands, and plan areas for farming, animal corridors, and fire guards. However, competition for resources has escalated in recent years. Traditional mechanisms that once existed to resolve conflicts—such as intermarriages between neighbouring tribal groups to promote peaceful coexistence—have become strained. Additionally, Sudan’s population is increasingly young and urbanized. One area of public life where women have been deeply engaged, albeit with little official recognition, is in promoting peace at both national and community levels.

Climate change and prolonged conflict exert almost identical impacts on the environment. Both degrade or deplete natural resources, which in turn affects people’s livelihoods and ability to survive. Poverty and the environment are inextricably linked—human deprivation and environmental degradation reinforce each other. Environmental issues are further exacerbated by inadequate urban planning and a lack of safety regulations for businesses and industries, leading to pollution and environmental degradation.

Sudan's cultural heritage is under threat from multiple forces, including climate change. Across the world, climate change and global warming are making traditional ways of life increasingly uncertain. Material culture, intangible practices, traditional knowledge, and cultural landscapes play a vital role in helping communities adapt to extreme and unpredictable climates. However, these rich traditions are themselves threatened by the unprecedented challenges of climate change. Museums serve as institutions where heritage is preserved for future generations, and they have a role in helping communities understand the impacts of climate change and appreciate the value of their cultural traditions for climate adaptation.

Environmental education is not yet fully integrated into Sudan’s formal education system, except at the basic education level. In 2022, the Western Sudan Community Museums project, as part of efforts to protect Sudanese heritage, developed the Green Heritage Programme with funding from the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund. This initiative raised awareness about the effects of climate change on communities in Sudan and its impact on both tangible and intangible heritage. The programme included a series of workshops in all three museums, a study on the impact of climate change on the intangible culture of nomads in Kordofan, and a major survey of Darfur’s monuments to assess climate change’s effects on the region’s heritage. Conducted by the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), the Afro-Asian Institute at the the University of Khartoum and the University of Nyala’s Darfur Heritage Department, the survey covered 180km and documented 12 major heritage sites in the Furnung, Tagabo, and Meidob Hills.

The project culminated in community exhibitions held at all three museums, providing spaces where diverse communities could come together to celebrate, enjoy, and learn from their unique and shared traditions—both today and for future generations.

Today, traditional leaders play important roles in environmental conservation. They enforce local customs that protect the environment, implement statutory laws to safeguard natural resources such as forests and rangelands, and plan areas for farming, animal corridors, and fire guards. However, competition for resources has escalated in recent years. Traditional mechanisms that once existed to resolve conflicts—such as intermarriages between neighbouring tribal groups to promote peaceful coexistence—have become strained. Additionally, Sudan’s population is increasingly young and urbanized. One area of public life where women have been deeply engaged, albeit with little official recognition, is in promoting peace at both national and community levels.

Climate change and prolonged conflict exert almost identical impacts on the environment. Both degrade or deplete natural resources, which in turn affects people’s livelihoods and ability to survive. Poverty and the environment are inextricably linked—human deprivation and environmental degradation reinforce each other. Environmental issues are further exacerbated by inadequate urban planning and a lack of safety regulations for businesses and industries, leading to pollution and environmental degradation.

Sudan's cultural heritage is under threat from multiple forces, including climate change. Across the world, climate change and global warming are making traditional ways of life increasingly uncertain. Material culture, intangible practices, traditional knowledge, and cultural landscapes play a vital role in helping communities adapt to extreme and unpredictable climates. However, these rich traditions are themselves threatened by the unprecedented challenges of climate change. Museums serve as institutions where heritage is preserved for future generations, and they have a role in helping communities understand the impacts of climate change and appreciate the value of their cultural traditions for climate adaptation.

Environmental education is not yet fully integrated into Sudan’s formal education system, except at the basic education level. In 2022, the Western Sudan Community Museums project, as part of efforts to protect Sudanese heritage, developed the Green Heritage Programme with funding from the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund. This initiative raised awareness about the effects of climate change on communities in Sudan and its impact on both tangible and intangible heritage. The programme included a series of workshops in all three museums, a study on the impact of climate change on the intangible culture of nomads in Kordofan, and a major survey of Darfur’s monuments to assess climate change’s effects on the region’s heritage. Conducted by the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), the Afro-Asian Institute at the the University of Khartoum and the University of Nyala’s Darfur Heritage Department, the survey covered 180km and documented 12 major heritage sites in the Furnung, Tagabo, and Meidob Hills.

The project culminated in community exhibitions held at all three museums, providing spaces where diverse communities could come together to celebrate, enjoy, and learn from their unique and shared traditions—both today and for future generations.

Lime Kilns In Sudan

Lime Kilns In Sudan

Question: What role should lime play in the future buildings of Sudan?

Sudan is rich in its variety of geological materials and many of these have been used since ancient times. Limestone is one of them. It is easily recognised in the form of stone blocks. Just think of ancient stone temples, columns or statues, or facing stones on more modern buildings. It is less recognizable when crushed or powdered and mixed with other materials like mud or sand. It is easily confused with cement because it looks almost the same – unsurprisingly as cement is made from crushed limestone – but it behaves very differently. It is important to know what these differences are when restoring traditional buildings like the Khalifa House in Omdurman if you want to avoid further damage. In Sudan, restoration techniques can lead to a wider appreciation of local resources and traditional building methods, and ways of using them for today’s climate that don’t cost the earth.

Imagine a Map of lime kilns in Sudan

Archaeologists have discovered that lime and ash were used to make floors many thousands of years ago, even before pottery kilns were invented. Lime is an alkaline material with disinfectant qualities so a good deterrent to bacteria and microorganisms. It is manufactured using fire or heat, which transforms its chemistry. Kilns provide an effective heat source and though they might differ in size and type, they are used to bake bread, fire pots or bricks, work glass, copper, bronze or iron, as well as burn lime. A map could be made of lime kilns in Sudan. It would plot a landscape of human activity that includes quarries, slaking pits, all types of built structures, as well as traces in agricultural land where lime is used as a soil improver.

A lime kiln is very similar to a pottery kiln but, instead of firing pots, pieces of limestone are burnt to produce a white crystalline solid called quicklime. For building purposes, the quicklime is slaked in water and left to rest until it forms a mouldable, easily worked putty which can be used to make plaster, mortar, or used as paint. It can be bulked out with other materials, notably mud or sand, adding to their qualities. Lime dries by absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere and chemically speaking turns back into limestone in a process called the lime-cycle. It retains a microscopic crystalline structure (useful in polished finishes) and lots of voids meaning it can breathe air and moisture. At the end of its life the whole process can start over again.

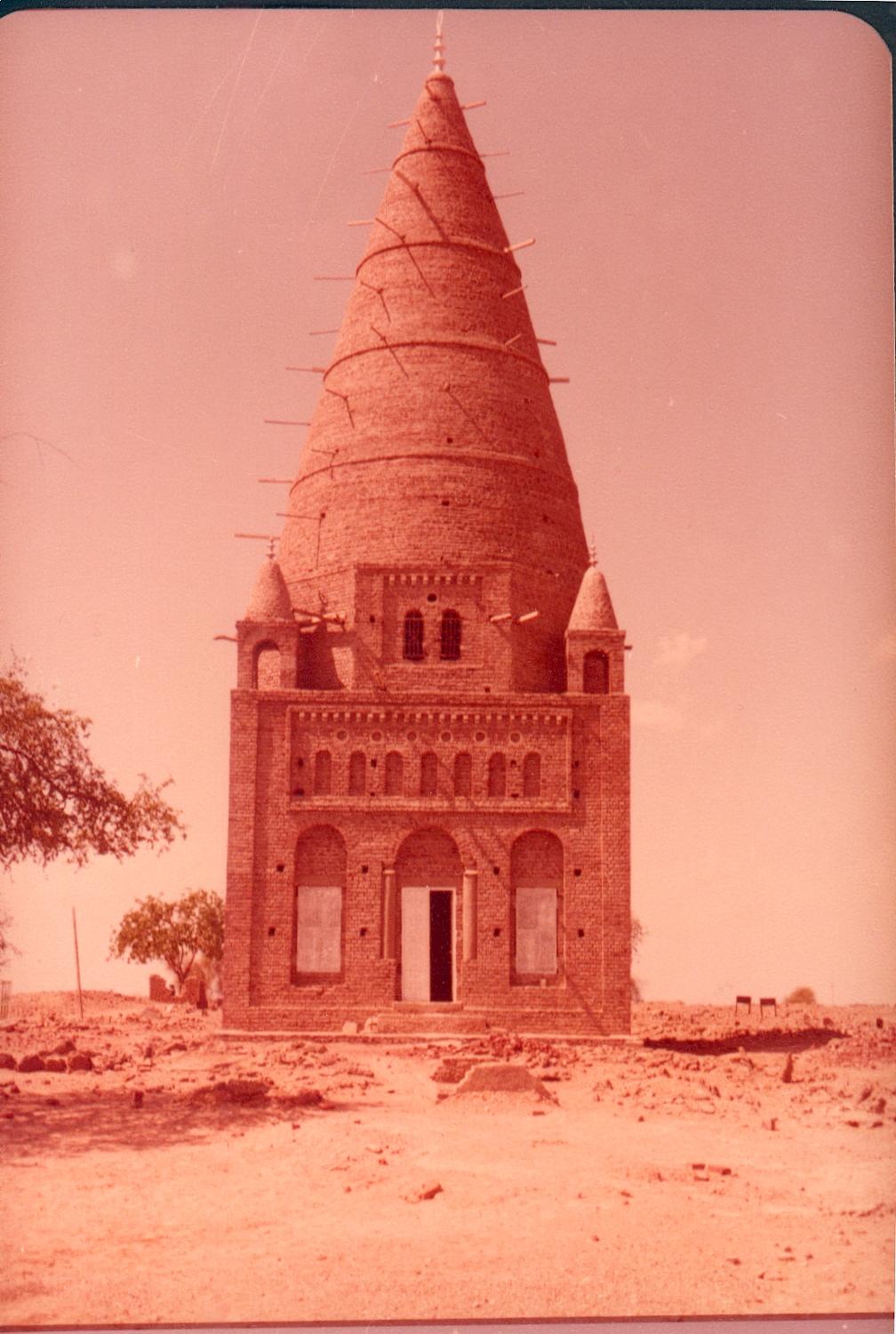

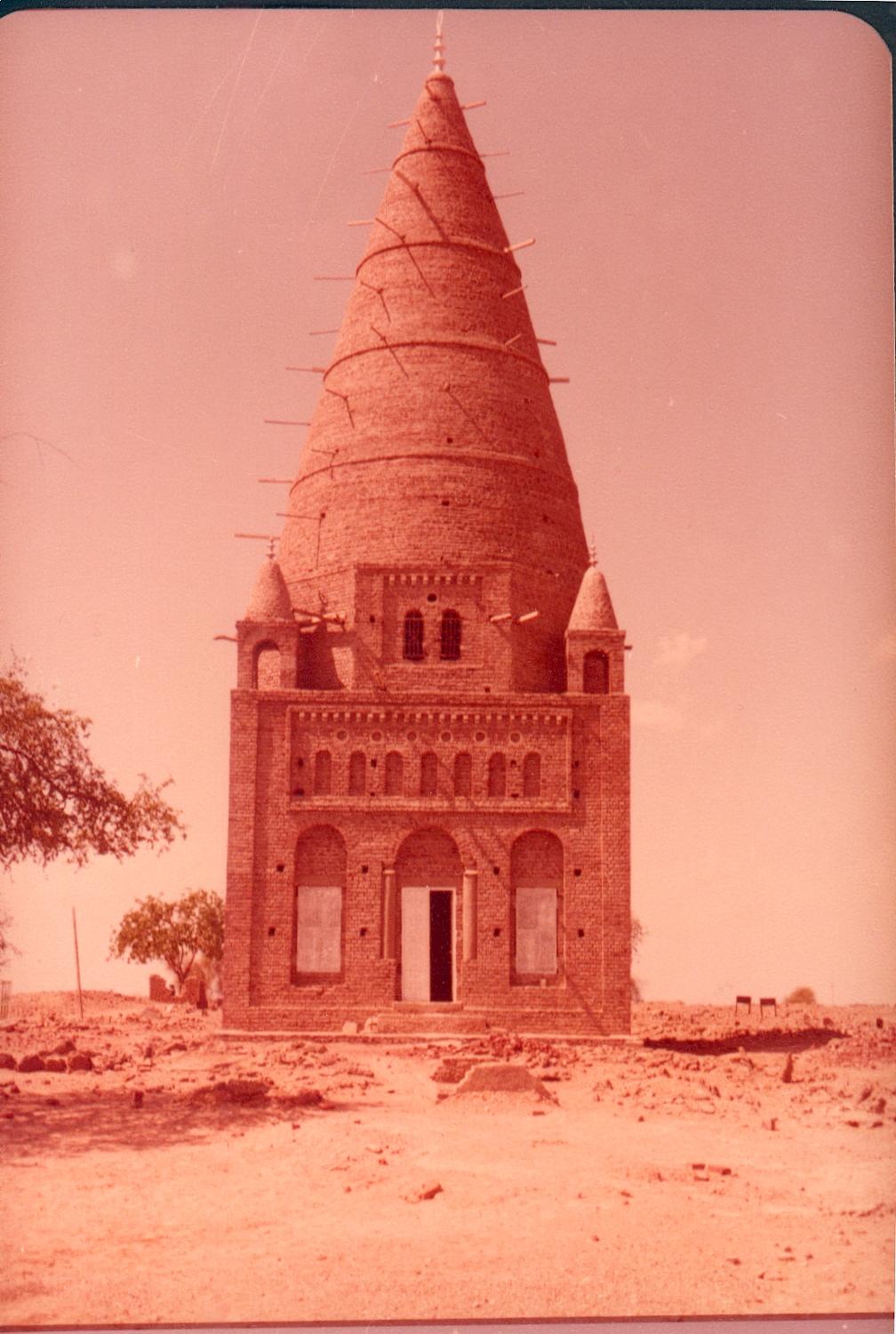

Timeline

If our map showed buildings using lime, it could be used to plot a history. It would tell us lime plaster was used in the stone-built Kushite pyramids and temples. During the Roman period it became popular on the Red Sea coast where there are large deposits of limestone reef beds, high humidity and seasonal rains. Here limestone and lime plasters became an enduring part of the Red Sea style of architecture, exemplified in the iconic buildings of Suakin. During the Christian period lime plaster and mortar were used in the fired brick churches of the Nile Valley, like the Cathedral in Faras and the churches in Dongola and Soba. Similar construction techniques were used in medieval gubbas and the mosques and palace buildings as well as across the Sahel in Darfur and Kordofan. The Ottoman occupation brought more elaborate lime plasterwork techniques and more widespread use until the twentieth century when it was replaced by cement.

Meanwhile, in the drier areas of Sudan, mud bricks, mud mortars were more popular. For example, the later gubbas in the north were built from mud brick and mortar, like the houses and villages. The lack of lime made buildings softer, but a drier atmosphere and reduced rainfall made this less important, until recently. Climate change has made rainfall in Sudan less predictable and more extreme.

Lime kilns, concrete and climate change

Kilns need something to burn and throughout Sudan’s history wood has been the main provider, so forests are needed. Deforestation in Sudan is the result of the drying climate, or an excessive human use of wood, or both. These factors suggest why and when lime stops being used as a building material unless there was an incentive to continue like on the humid Red Sea coast or further south where there are still forests. Our imagined map of lime kilns would show many ruins of kilns in dry or deforested areas. However, it will also show a new breed of limestone burning kilns in the form of modern factories producing cement. These favour water locations over forests.

In Sudan, like most of the world, lime production has been overtaken by cement production as concrete has become the number one building material. Its impact on natural and built landscapes is so enormous it is used as the visual marker of the Anthropocene age, our own geological time frame where human activity is the dominant influence on climate and the environment. Worldwide this highly refined product has grown to become the biggest consumable after water, the consumption of which it helps drive. Cement is used in infrastructure projects and buildings of all kinds because it has the advantage of strength, durability, and fast production. It is seen as utilitarian because it lends itself to the mass production of office and housing units. It is also fashionable. Concrete is used as a symbol of being modern and it lends itself to realizable fantasy projects, nothing seems too big, too tall or too weird in shape.

In 2018 Sudan was described in SUDANOW magazine as having a booming cement industry with a bright future. The limestone needed was available in many parts of the country and the Nile provided water. The first dam built in Sudan, the Sennar Dam (1925), used uncoursed granite bedded in cement from its on-the-spot new cement factory turning out 1,000 tons of cement a week.

Concrete, however, has its downsides. The production of cement is high on the list of causes of climate change due to its considerable use of water, greenhouse gas emissions (1kg cement = 1kg CO2), fossil fuel energy consumption and environmental damage. However, it was the historic building restoration lobby that first raised the alarm. Historic buildings that had been restored using cement products were failing faster and being damaged by the cement. For although cement seemed to be like lime but better, as it is made from the same basic materials and heating processes, it turns out that it is different rather than better. The way it is made produces different material outcomes.

Khalifa House restoration

The lime kilns in Omdurman date to the Mahdi period. The Khalifa wanted to build defences strong enough to withstand modern weaponry. The walls in front, and the massive enclosure walls around the Mulazmeen quarter, were 6m high and built with lime and stone. These are the materials used in the first and second phase of construction of the Khalifa House.

The restoration of the Khalifa House in Omdurman started in 2018. The one material not used to restore the building was cement, in fact nearly all traces of it were carefully removed and replaced with lime-based plaster. This was a lot of work as in previous years many of the walls had been repaired and rendered with cement in the belief that they would be better protected. However, because cement is a much harder and an impervious material, it transfers all the problems of movement and moisture to the bricks, mud or stone, and they decay much faster. To restore the Khalifa House properly the builders had to source the lime, slake it in pits and learn the traditional techniques. They did a beautiful job.

The same learning is now being utilised in the ongoing Peace Garden project in Kassala where twelve different house types from all over Sudan are being erected. The team is looking carefully at the use of lime in the mud construction as a way of improving resilience to heavy rainfalls. There are many examples in Sudan of mudbrick buildings that have survived for centuries as well as in other countries around the world, so what is their secret?

Factors to consider

In 2007 work started on the Al Shamal cement factory in Al Damer. Equipped with the latest European technology it also has a solar power plant to supply the factory with lots of clean electricity. The ‘bright future’ claimed for Sudan’s cement industry anticipated two things, Sudan’s participation in a booming market and the development of Sudan itself. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the last empty spaces on the concrete industry project map.

The problem with cement-based materials is they start with a different attitude to life. They are strong and quicker to employ, but less adjusted to living in a natural landscape. They need an extensive infrastructure to work, from quarries to roads, to water and energy, and industrialised systems of supply and demand.

Traditional building techniques in Sudan, on the other hand, are closely tied to the availability of natural resources, local transport, local climate, livelihoods and culture. Lime based materials can help preserve the ecology of living landscapes. Moreover, lime's ability to control moisture means it is compatible with low-energy, sustainable materials, such as water reed, straw, hemp, timber and clay. Lime rather than cement is burnt at 900 degrees rather than 1300 degrees, so less onerous energy-wise and, looking forwards, parabolic solar collectors can be used to fire solar rotary kilns.

The map of lime kilns in Sudan shows the landscape is not empty but full of traditional building types that have been adapting to climate change over a long history. They could play a significant role in adapting to climate change in the future. Not everything is better built in concrete.

Cover picture: Suakin © Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez

Question: What role should lime play in the future buildings of Sudan?

Sudan is rich in its variety of geological materials and many of these have been used since ancient times. Limestone is one of them. It is easily recognised in the form of stone blocks. Just think of ancient stone temples, columns or statues, or facing stones on more modern buildings. It is less recognizable when crushed or powdered and mixed with other materials like mud or sand. It is easily confused with cement because it looks almost the same – unsurprisingly as cement is made from crushed limestone – but it behaves very differently. It is important to know what these differences are when restoring traditional buildings like the Khalifa House in Omdurman if you want to avoid further damage. In Sudan, restoration techniques can lead to a wider appreciation of local resources and traditional building methods, and ways of using them for today’s climate that don’t cost the earth.

Imagine a Map of lime kilns in Sudan

Archaeologists have discovered that lime and ash were used to make floors many thousands of years ago, even before pottery kilns were invented. Lime is an alkaline material with disinfectant qualities so a good deterrent to bacteria and microorganisms. It is manufactured using fire or heat, which transforms its chemistry. Kilns provide an effective heat source and though they might differ in size and type, they are used to bake bread, fire pots or bricks, work glass, copper, bronze or iron, as well as burn lime. A map could be made of lime kilns in Sudan. It would plot a landscape of human activity that includes quarries, slaking pits, all types of built structures, as well as traces in agricultural land where lime is used as a soil improver.

A lime kiln is very similar to a pottery kiln but, instead of firing pots, pieces of limestone are burnt to produce a white crystalline solid called quicklime. For building purposes, the quicklime is slaked in water and left to rest until it forms a mouldable, easily worked putty which can be used to make plaster, mortar, or used as paint. It can be bulked out with other materials, notably mud or sand, adding to their qualities. Lime dries by absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere and chemically speaking turns back into limestone in a process called the lime-cycle. It retains a microscopic crystalline structure (useful in polished finishes) and lots of voids meaning it can breathe air and moisture. At the end of its life the whole process can start over again.

Timeline

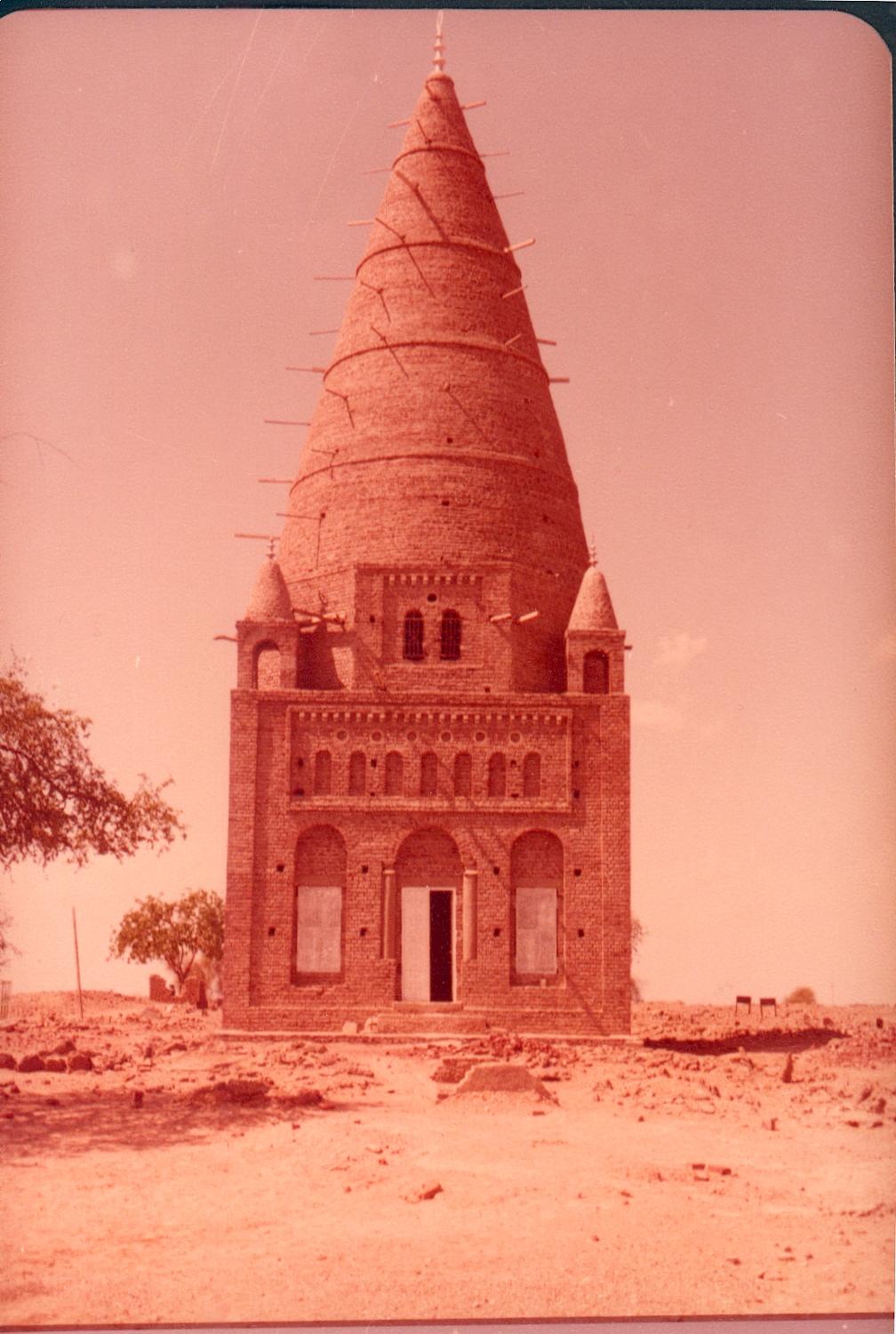

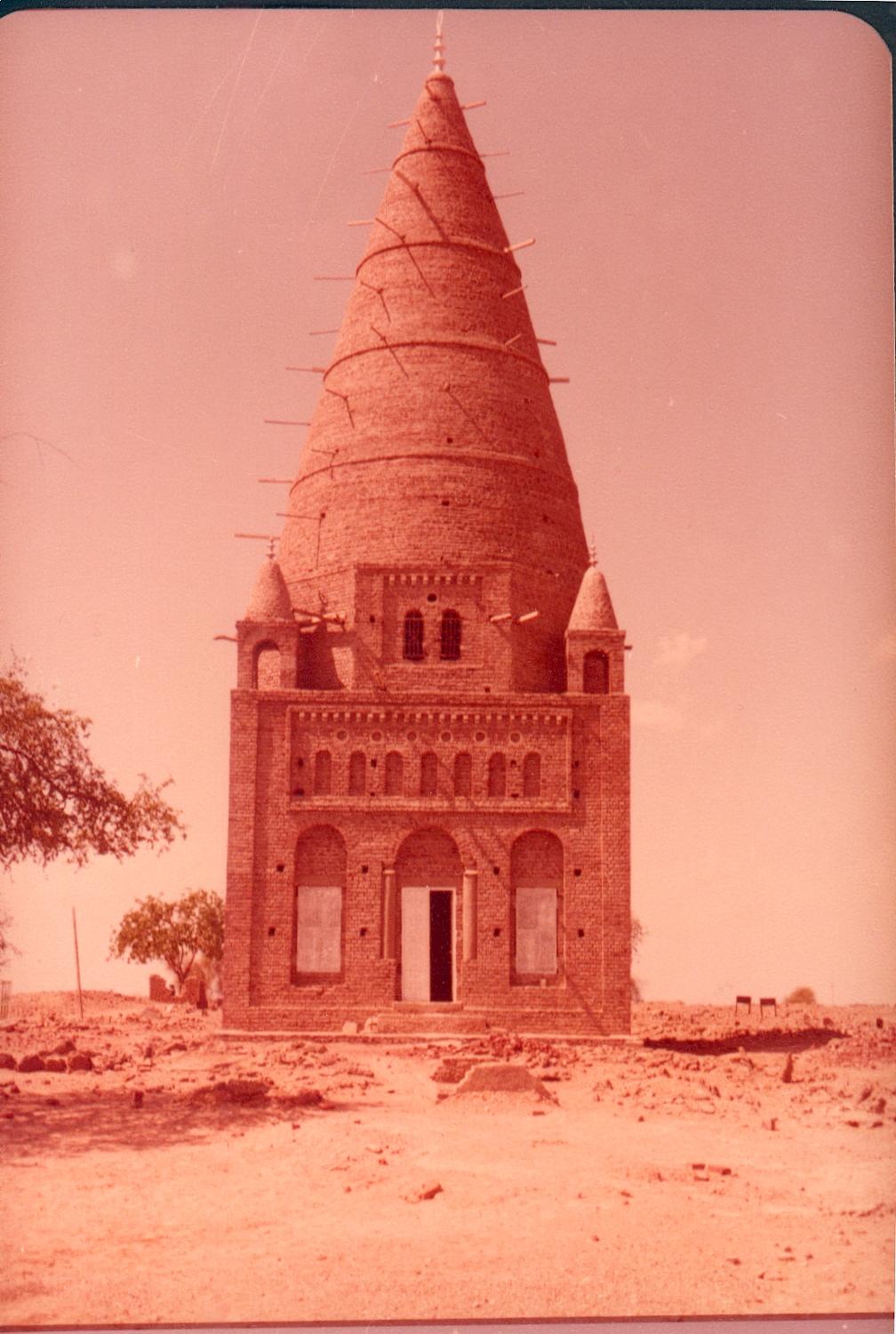

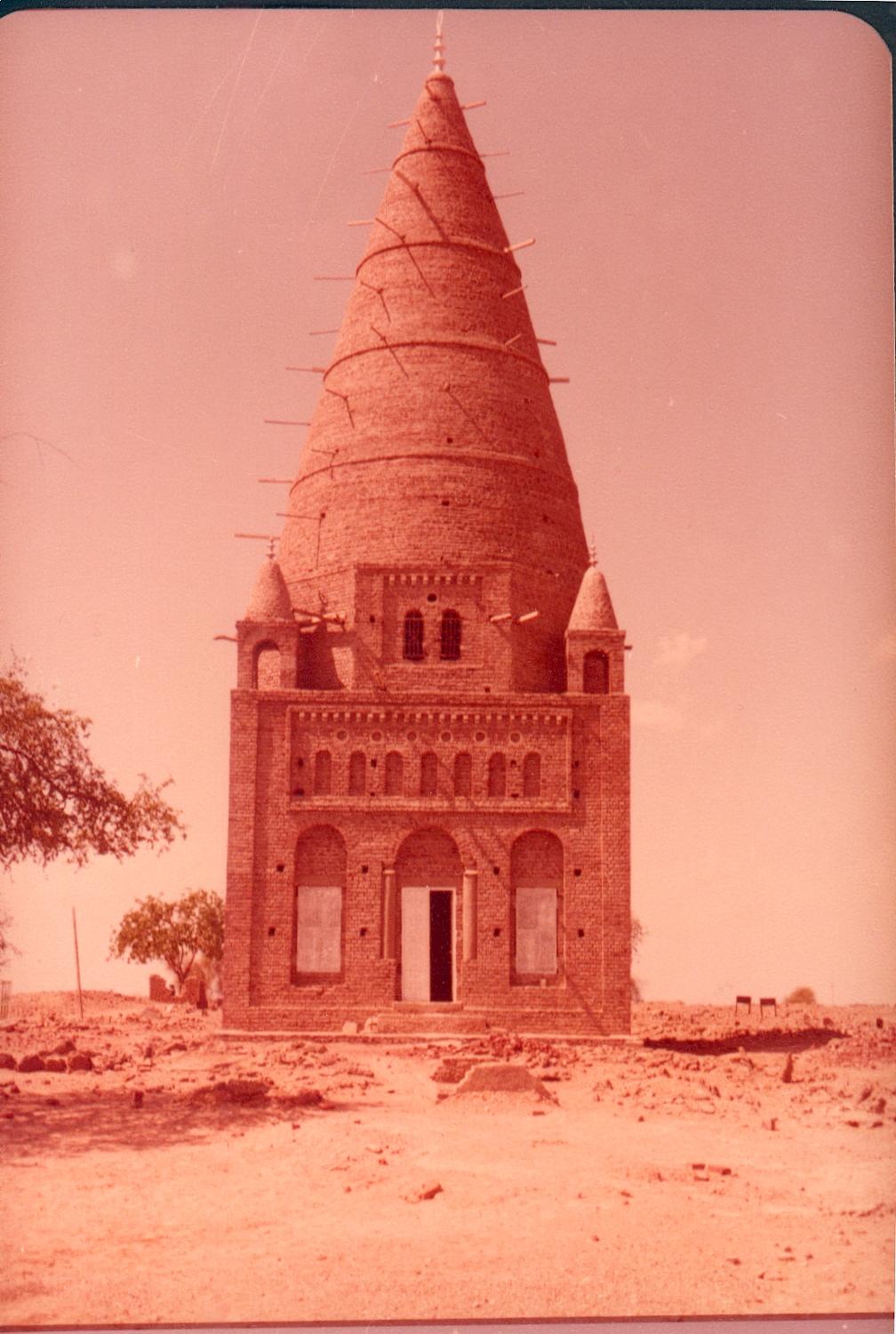

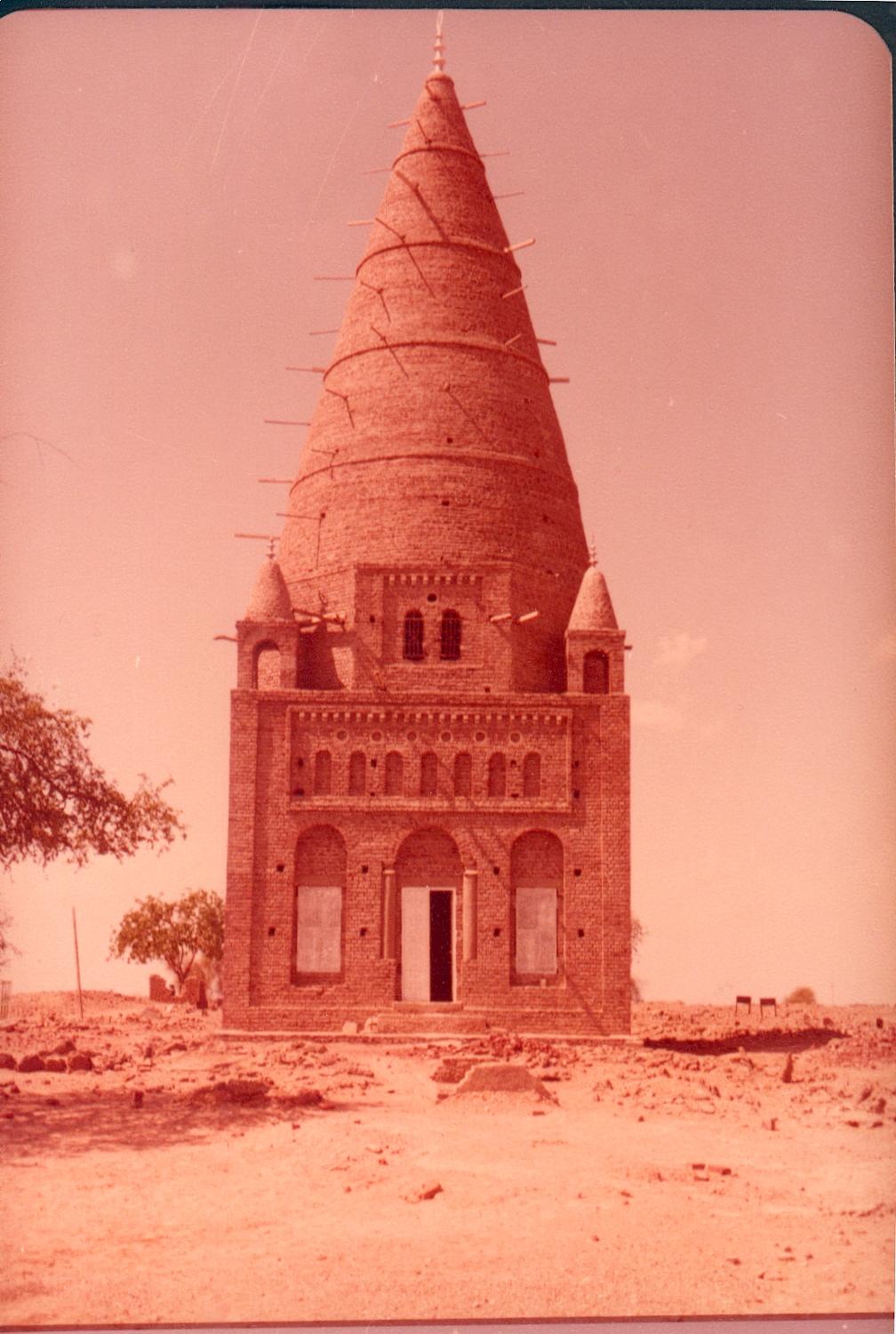

If our map showed buildings using lime, it could be used to plot a history. It would tell us lime plaster was used in the stone-built Kushite pyramids and temples. During the Roman period it became popular on the Red Sea coast where there are large deposits of limestone reef beds, high humidity and seasonal rains. Here limestone and lime plasters became an enduring part of the Red Sea style of architecture, exemplified in the iconic buildings of Suakin. During the Christian period lime plaster and mortar were used in the fired brick churches of the Nile Valley, like the Cathedral in Faras and the churches in Dongola and Soba. Similar construction techniques were used in medieval gubbas and the mosques and palace buildings as well as across the Sahel in Darfur and Kordofan. The Ottoman occupation brought more elaborate lime plasterwork techniques and more widespread use until the twentieth century when it was replaced by cement.

Meanwhile, in the drier areas of Sudan, mud bricks, mud mortars were more popular. For example, the later gubbas in the north were built from mud brick and mortar, like the houses and villages. The lack of lime made buildings softer, but a drier atmosphere and reduced rainfall made this less important, until recently. Climate change has made rainfall in Sudan less predictable and more extreme.

Lime kilns, concrete and climate change

Kilns need something to burn and throughout Sudan’s history wood has been the main provider, so forests are needed. Deforestation in Sudan is the result of the drying climate, or an excessive human use of wood, or both. These factors suggest why and when lime stops being used as a building material unless there was an incentive to continue like on the humid Red Sea coast or further south where there are still forests. Our imagined map of lime kilns would show many ruins of kilns in dry or deforested areas. However, it will also show a new breed of limestone burning kilns in the form of modern factories producing cement. These favour water locations over forests.

In Sudan, like most of the world, lime production has been overtaken by cement production as concrete has become the number one building material. Its impact on natural and built landscapes is so enormous it is used as the visual marker of the Anthropocene age, our own geological time frame where human activity is the dominant influence on climate and the environment. Worldwide this highly refined product has grown to become the biggest consumable after water, the consumption of which it helps drive. Cement is used in infrastructure projects and buildings of all kinds because it has the advantage of strength, durability, and fast production. It is seen as utilitarian because it lends itself to the mass production of office and housing units. It is also fashionable. Concrete is used as a symbol of being modern and it lends itself to realizable fantasy projects, nothing seems too big, too tall or too weird in shape.

In 2018 Sudan was described in SUDANOW magazine as having a booming cement industry with a bright future. The limestone needed was available in many parts of the country and the Nile provided water. The first dam built in Sudan, the Sennar Dam (1925), used uncoursed granite bedded in cement from its on-the-spot new cement factory turning out 1,000 tons of cement a week.

Concrete, however, has its downsides. The production of cement is high on the list of causes of climate change due to its considerable use of water, greenhouse gas emissions (1kg cement = 1kg CO2), fossil fuel energy consumption and environmental damage. However, it was the historic building restoration lobby that first raised the alarm. Historic buildings that had been restored using cement products were failing faster and being damaged by the cement. For although cement seemed to be like lime but better, as it is made from the same basic materials and heating processes, it turns out that it is different rather than better. The way it is made produces different material outcomes.

Khalifa House restoration

The lime kilns in Omdurman date to the Mahdi period. The Khalifa wanted to build defences strong enough to withstand modern weaponry. The walls in front, and the massive enclosure walls around the Mulazmeen quarter, were 6m high and built with lime and stone. These are the materials used in the first and second phase of construction of the Khalifa House.

The restoration of the Khalifa House in Omdurman started in 2018. The one material not used to restore the building was cement, in fact nearly all traces of it were carefully removed and replaced with lime-based plaster. This was a lot of work as in previous years many of the walls had been repaired and rendered with cement in the belief that they would be better protected. However, because cement is a much harder and an impervious material, it transfers all the problems of movement and moisture to the bricks, mud or stone, and they decay much faster. To restore the Khalifa House properly the builders had to source the lime, slake it in pits and learn the traditional techniques. They did a beautiful job.

The same learning is now being utilised in the ongoing Peace Garden project in Kassala where twelve different house types from all over Sudan are being erected. The team is looking carefully at the use of lime in the mud construction as a way of improving resilience to heavy rainfalls. There are many examples in Sudan of mudbrick buildings that have survived for centuries as well as in other countries around the world, so what is their secret?

Factors to consider

In 2007 work started on the Al Shamal cement factory in Al Damer. Equipped with the latest European technology it also has a solar power plant to supply the factory with lots of clean electricity. The ‘bright future’ claimed for Sudan’s cement industry anticipated two things, Sudan’s participation in a booming market and the development of Sudan itself. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the last empty spaces on the concrete industry project map.

The problem with cement-based materials is they start with a different attitude to life. They are strong and quicker to employ, but less adjusted to living in a natural landscape. They need an extensive infrastructure to work, from quarries to roads, to water and energy, and industrialised systems of supply and demand.

Traditional building techniques in Sudan, on the other hand, are closely tied to the availability of natural resources, local transport, local climate, livelihoods and culture. Lime based materials can help preserve the ecology of living landscapes. Moreover, lime's ability to control moisture means it is compatible with low-energy, sustainable materials, such as water reed, straw, hemp, timber and clay. Lime rather than cement is burnt at 900 degrees rather than 1300 degrees, so less onerous energy-wise and, looking forwards, parabolic solar collectors can be used to fire solar rotary kilns.

The map of lime kilns in Sudan shows the landscape is not empty but full of traditional building types that have been adapting to climate change over a long history. They could play a significant role in adapting to climate change in the future. Not everything is better built in concrete.

Cover picture: Suakin © Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez

Question: What role should lime play in the future buildings of Sudan?

Sudan is rich in its variety of geological materials and many of these have been used since ancient times. Limestone is one of them. It is easily recognised in the form of stone blocks. Just think of ancient stone temples, columns or statues, or facing stones on more modern buildings. It is less recognizable when crushed or powdered and mixed with other materials like mud or sand. It is easily confused with cement because it looks almost the same – unsurprisingly as cement is made from crushed limestone – but it behaves very differently. It is important to know what these differences are when restoring traditional buildings like the Khalifa House in Omdurman if you want to avoid further damage. In Sudan, restoration techniques can lead to a wider appreciation of local resources and traditional building methods, and ways of using them for today’s climate that don’t cost the earth.

Imagine a Map of lime kilns in Sudan

Archaeologists have discovered that lime and ash were used to make floors many thousands of years ago, even before pottery kilns were invented. Lime is an alkaline material with disinfectant qualities so a good deterrent to bacteria and microorganisms. It is manufactured using fire or heat, which transforms its chemistry. Kilns provide an effective heat source and though they might differ in size and type, they are used to bake bread, fire pots or bricks, work glass, copper, bronze or iron, as well as burn lime. A map could be made of lime kilns in Sudan. It would plot a landscape of human activity that includes quarries, slaking pits, all types of built structures, as well as traces in agricultural land where lime is used as a soil improver.

A lime kiln is very similar to a pottery kiln but, instead of firing pots, pieces of limestone are burnt to produce a white crystalline solid called quicklime. For building purposes, the quicklime is slaked in water and left to rest until it forms a mouldable, easily worked putty which can be used to make plaster, mortar, or used as paint. It can be bulked out with other materials, notably mud or sand, adding to their qualities. Lime dries by absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere and chemically speaking turns back into limestone in a process called the lime-cycle. It retains a microscopic crystalline structure (useful in polished finishes) and lots of voids meaning it can breathe air and moisture. At the end of its life the whole process can start over again.

Timeline

If our map showed buildings using lime, it could be used to plot a history. It would tell us lime plaster was used in the stone-built Kushite pyramids and temples. During the Roman period it became popular on the Red Sea coast where there are large deposits of limestone reef beds, high humidity and seasonal rains. Here limestone and lime plasters became an enduring part of the Red Sea style of architecture, exemplified in the iconic buildings of Suakin. During the Christian period lime plaster and mortar were used in the fired brick churches of the Nile Valley, like the Cathedral in Faras and the churches in Dongola and Soba. Similar construction techniques were used in medieval gubbas and the mosques and palace buildings as well as across the Sahel in Darfur and Kordofan. The Ottoman occupation brought more elaborate lime plasterwork techniques and more widespread use until the twentieth century when it was replaced by cement.

Meanwhile, in the drier areas of Sudan, mud bricks, mud mortars were more popular. For example, the later gubbas in the north were built from mud brick and mortar, like the houses and villages. The lack of lime made buildings softer, but a drier atmosphere and reduced rainfall made this less important, until recently. Climate change has made rainfall in Sudan less predictable and more extreme.

Lime kilns, concrete and climate change

Kilns need something to burn and throughout Sudan’s history wood has been the main provider, so forests are needed. Deforestation in Sudan is the result of the drying climate, or an excessive human use of wood, or both. These factors suggest why and when lime stops being used as a building material unless there was an incentive to continue like on the humid Red Sea coast or further south where there are still forests. Our imagined map of lime kilns would show many ruins of kilns in dry or deforested areas. However, it will also show a new breed of limestone burning kilns in the form of modern factories producing cement. These favour water locations over forests.

In Sudan, like most of the world, lime production has been overtaken by cement production as concrete has become the number one building material. Its impact on natural and built landscapes is so enormous it is used as the visual marker of the Anthropocene age, our own geological time frame where human activity is the dominant influence on climate and the environment. Worldwide this highly refined product has grown to become the biggest consumable after water, the consumption of which it helps drive. Cement is used in infrastructure projects and buildings of all kinds because it has the advantage of strength, durability, and fast production. It is seen as utilitarian because it lends itself to the mass production of office and housing units. It is also fashionable. Concrete is used as a symbol of being modern and it lends itself to realizable fantasy projects, nothing seems too big, too tall or too weird in shape.

In 2018 Sudan was described in SUDANOW magazine as having a booming cement industry with a bright future. The limestone needed was available in many parts of the country and the Nile provided water. The first dam built in Sudan, the Sennar Dam (1925), used uncoursed granite bedded in cement from its on-the-spot new cement factory turning out 1,000 tons of cement a week.

Concrete, however, has its downsides. The production of cement is high on the list of causes of climate change due to its considerable use of water, greenhouse gas emissions (1kg cement = 1kg CO2), fossil fuel energy consumption and environmental damage. However, it was the historic building restoration lobby that first raised the alarm. Historic buildings that had been restored using cement products were failing faster and being damaged by the cement. For although cement seemed to be like lime but better, as it is made from the same basic materials and heating processes, it turns out that it is different rather than better. The way it is made produces different material outcomes.

Khalifa House restoration

The lime kilns in Omdurman date to the Mahdi period. The Khalifa wanted to build defences strong enough to withstand modern weaponry. The walls in front, and the massive enclosure walls around the Mulazmeen quarter, were 6m high and built with lime and stone. These are the materials used in the first and second phase of construction of the Khalifa House.

The restoration of the Khalifa House in Omdurman started in 2018. The one material not used to restore the building was cement, in fact nearly all traces of it were carefully removed and replaced with lime-based plaster. This was a lot of work as in previous years many of the walls had been repaired and rendered with cement in the belief that they would be better protected. However, because cement is a much harder and an impervious material, it transfers all the problems of movement and moisture to the bricks, mud or stone, and they decay much faster. To restore the Khalifa House properly the builders had to source the lime, slake it in pits and learn the traditional techniques. They did a beautiful job.

The same learning is now being utilised in the ongoing Peace Garden project in Kassala where twelve different house types from all over Sudan are being erected. The team is looking carefully at the use of lime in the mud construction as a way of improving resilience to heavy rainfalls. There are many examples in Sudan of mudbrick buildings that have survived for centuries as well as in other countries around the world, so what is their secret?

Factors to consider

In 2007 work started on the Al Shamal cement factory in Al Damer. Equipped with the latest European technology it also has a solar power plant to supply the factory with lots of clean electricity. The ‘bright future’ claimed for Sudan’s cement industry anticipated two things, Sudan’s participation in a booming market and the development of Sudan itself. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the last empty spaces on the concrete industry project map.

The problem with cement-based materials is they start with a different attitude to life. They are strong and quicker to employ, but less adjusted to living in a natural landscape. They need an extensive infrastructure to work, from quarries to roads, to water and energy, and industrialised systems of supply and demand.

Traditional building techniques in Sudan, on the other hand, are closely tied to the availability of natural resources, local transport, local climate, livelihoods and culture. Lime based materials can help preserve the ecology of living landscapes. Moreover, lime's ability to control moisture means it is compatible with low-energy, sustainable materials, such as water reed, straw, hemp, timber and clay. Lime rather than cement is burnt at 900 degrees rather than 1300 degrees, so less onerous energy-wise and, looking forwards, parabolic solar collectors can be used to fire solar rotary kilns.

The map of lime kilns in Sudan shows the landscape is not empty but full of traditional building types that have been adapting to climate change over a long history. They could play a significant role in adapting to climate change in the future. Not everything is better built in concrete.

Cover picture: Suakin © Issam Ahmed Abdelhafiez

Mud architecture in Dagarta Island

Mud architecture in Dagarta Island

Introduction:

Islanders use the names Dagarta or Dagarti for their home. The names are made up of words in the the Fadija language including ‘Arti’ meaning Island and ‘Dagar’ which can mean ‘transporting a bride to her husband’s home’ or ‘the practice of tying a pole in the river to gather silt and create a man-made sedimentary island’

Dagarta Island is located in northern Sudan and falls under the administration of Kerma city in the Burqīq locality. It is believed to have been inhabited for thousands of years, with its residents living in the centre of the island, while the agricultural lands are situated on its outskirts.

Before the war, the island's population ranged between 600 and 700 people. However, due to displacement from other areas in Sudan, approximately 340 people—mostly original inhabitants—have returned to their abandoned homes.

(Introduction taken from an article in Atar Magazine, Issue 19, published on February 29, 2024.)

On mud Architecture:

The experience of living in mud-brick buildings varies depending on several factors. For example, where is the building located? Is it in a humid or dry area (such as a region affected by dam-related climate changes)? What is the nature of the soil there (sandy, clay, or rocky)? And finally, who is evaluating the experience—Is it a native of the area or someone displaced due to the recent war? Individual differences also play a role; what suits one person may, or may not, suit another.

However, let’s agree that the displacement crisis has a much darker side than voluntary return to one’s home and birthplace. There is always a romanticized notion attached to returning to the countryside—a place of pristine nature, healthy food, and a natural way of life that city dwellers long for. But behind this unspoiled environment lies significant underdevelopment and poverty, equally affecting all regions of Sudan.

In one of my past fantasies, I imagined owning a beautifully decorated mud-brick house in the countryside, with a small farm growing seasonal crops and fruit trees for self-sufficiency. I saw this as a form of atonement for my life in a Sudanese city that distorted the ideas of citizenship, beauty, and civilization—a search for my lost identity and an unconditional friendship with the environment. However, this dream shattered before my eyes after living in these homes for many months, experiencing both winter and summer. I found myself asking a strange question: Why is mud-brick architecture in Dagarta Island still in use and why has it not just become an extinct heritage practice? How beautiful it is to read about it in reports and studies, and how lovely its images appear online—yet how harsh it is to live inside these buildings as they are, without modern conveniences.

The lifestyle and daily tasks assigned to men and women on the island is key to understanding how these buildings are used, as frequent social visits, working in farms and being in outdoor spaces help ease the severity of the summer heat and winter cold that you can experience in these buildings. The island’s residents don’t stay in their rooms all day, as I did, being a newcomer from the city.

Another challenge of this architecture is its durability—it is constantly exposed to destruction and turns into ruins just a few years after being abandoned, unlike buildings made of other materials (stone, cement, or red brick). Regular maintenance is an essential part of life on the island, as homes are treated like living beings with their own needs, and residents do not complain about taking care of them. Interestingly, abandoned buildings played a crucial role in housing displaced people and returning islanders during the war. Due to the simplicity of construction techniques, the ruins were quickly restored to accommodate the large influx of people.

Building mud houses on Dagarta Island was never a matter of choice. The island’s isolation and the difficulty of transporting modern construction materials, along with limited space preventing the construction of brick kilns without causing health hazards, made mud-brick construction the only viable option. Of course, some Islanders can afford to transport these materials, but only very few. Only major projects funded by the government or private sources—such as the only primary school, the medical centre, and the two mosques (referred to as “Qibli” and “Bahri,” meaning south and north of the island)—were built using red bricks and finished with modern materials.

The economy of most island residents depends on seasonal agriculture, growing crops such as wheat, fava beans, and dates, while partially relying on financial support from their expatriate children. In recent years, fertilizers and pesticides have become essential to ensure successful harvests, as the nutrient-rich silt that once replenished the soil has significantly declined as a result of the construction of the Merowe Dam. Additionally, the selling price of crops for islanders is much lower compared to mainland residents, as farmers must bear the cost of transporting their produce across the river. These economic factors must be considered when asking why most houses are still built using traditional methods and why they lack modern cooling and heating systems to ease the hardships of extreme weather.

One positive government-provided service is the water network, which has connected pipes to every home. However, there is also a downside: before this network, women would go to the Nile to fetch water, turning it into a social activity. All elderly women on the island know how to swim. They did not stay indoors suffering from the intense heat during the day. Thus when we look at any solution offered for an age-old problem, we realize it often brings unintended consequences.

What Does the House Consist Of?

A typical mud house consists of rooms, barandat, verandas, a kitchen, and a storage area. Additional structures outside the main enclosure include an outdoor kitchen for making traditional bread if space inside the house is limited, a latrine, a pigeon tower, a rakuba (a shaded sitting area for men with chairs and beds for receiving guests), an outdoor traditional clay water dispenser mazyara, and a platform for storing produce rasa and grain silo gosayba.

Regarding sanitation, there is no sewage network due to the island's small size, nor are there sewage suction tanks, as there are no motorized vehicles on the island—except for one plow owned collectively by the island’s farmers. The common solution is pit latrines, it’s a system that consists of digging a pit behind the bathroom connected with PVC drainage pipes and a ventilation outlet. As it’s a dry system, water usage is minimized to slow the filling of the well. Water from washing drains into an external pit, which is later emptied. When a washroom pit fills up, the washroom is abandoned, and a new one is built with a new pit. If space is limited, the washroom may be built outside the house. Dishwashing water is collected in a basin and bucket, then poured into the street, directed to an alley, or drained onto an empty plot of land.

Building Materials and Construction

The first components of the house, mud bricks, are shaped and left to dry in an open area, ideally near the intended house site and an area free of crops. Sometimes, the bricks are made in a farm that hasn’t yet been plowed for the new season. In one unfortunate incident, a large quantity of bricks was flooded because the farmer responsible for irrigating his crops and closing the canal at specific times overslept that night. The brickmaker woke up to a sad reality as all his efforts had gone to waste. Brickmaking is paid work, but the homeowner may do it themselves to reduce costs, as well as transport the bricks by cart from the moulding site to the intended house plot. Beyond that, the actual construction is a communal effort nafir—men gather to build the house and roof it, while women later apply a finishing layer of plaster with sifted clay and gum arabic for durability. All buildings on the island are single-story structures.

What Are the Building Materials?

Building materials include:

- Mud bricks

- Mud mortar

- Interior and exterior plaster made of mud

- Stones placed atop walls to support roof beams

- Wooden beams made of tree trunks for the roof

- Roof covering of palm fronds or reeds, sealed with a layer of mud

- Aluminum sheets (called zinc) and iron pipes, eliminating the need for the ventilation gap between the wall and ceiling, which prevents termites from reaching and damaging the roof.

Every year, the house’s walls and floors are replastered at least twice because the outer protective layer is affected by weather conditions. This process also seals holes that might allow scorpions or other pests to enter. Because the island is affected by termites, even with carefully sieved soil, traces of straw in the mud serve as food for these destructive insects. The solution for furniture is to use metal pieces or to elevate wooden items on stone or plastic bases.

The variation in house colours, despite being built from the same earth, results from differences in the amount of gum arabic added to the mud mixture. This substance enhances adhesion and durability, and its varying proportions create different shades—from dark brown to lighter earthy tones.

Climate Challenges and Adaptation

Extreme climate changes must be considered. Reports on the El Niño phenomenon place Sudan among the most affected countries. During the 2024 rainy season, many homes in mainland areas opposite the island collapsed due to their location in natural flood zones. Unlike the typically arid climate, sudden heavy rains have become increasingly common in recent years. The cost of regular maintenance—or, in the worst case, relocating buildings to higher ground—has become an inevitable necessity. Fortunately, no houses on the island itself collapsed, although strong winds accompanying the rains did blow off zinc roofs. Because of the varied elevations of buildings and streets, water did not remain trapped inside homes for long.

As I write this in the third week of February 2025, islanders are enduring an extreme cold wave and have resorted to using traditional heating methods—placing a metal basin filled with burning coals inside their rooms. Meanwhile last summer record-breaking temperatures were recorded reaching an average of 46°C in May and June.

Accepting these climate changes as a new reality, rather than as isolated occurrences, could be the first step towards sustainable architectural solutions using local materials—making life in a mud house safe throughout the seasons.

Header picture and all Gallery pictures: Dagarta Island, North Sudan, 2024 © Aya Sinada

Introduction:

Islanders use the names Dagarta or Dagarti for their home. The names are made up of words in the the Fadija language including ‘Arti’ meaning Island and ‘Dagar’ which can mean ‘transporting a bride to her husband’s home’ or ‘the practice of tying a pole in the river to gather silt and create a man-made sedimentary island’

Dagarta Island is located in northern Sudan and falls under the administration of Kerma city in the Burqīq locality. It is believed to have been inhabited for thousands of years, with its residents living in the centre of the island, while the agricultural lands are situated on its outskirts.

Before the war, the island's population ranged between 600 and 700 people. However, due to displacement from other areas in Sudan, approximately 340 people—mostly original inhabitants—have returned to their abandoned homes.

(Introduction taken from an article in Atar Magazine, Issue 19, published on February 29, 2024.)

On mud Architecture:

The experience of living in mud-brick buildings varies depending on several factors. For example, where is the building located? Is it in a humid or dry area (such as a region affected by dam-related climate changes)? What is the nature of the soil there (sandy, clay, or rocky)? And finally, who is evaluating the experience—Is it a native of the area or someone displaced due to the recent war? Individual differences also play a role; what suits one person may, or may not, suit another.

However, let’s agree that the displacement crisis has a much darker side than voluntary return to one’s home and birthplace. There is always a romanticized notion attached to returning to the countryside—a place of pristine nature, healthy food, and a natural way of life that city dwellers long for. But behind this unspoiled environment lies significant underdevelopment and poverty, equally affecting all regions of Sudan.

In one of my past fantasies, I imagined owning a beautifully decorated mud-brick house in the countryside, with a small farm growing seasonal crops and fruit trees for self-sufficiency. I saw this as a form of atonement for my life in a Sudanese city that distorted the ideas of citizenship, beauty, and civilization—a search for my lost identity and an unconditional friendship with the environment. However, this dream shattered before my eyes after living in these homes for many months, experiencing both winter and summer. I found myself asking a strange question: Why is mud-brick architecture in Dagarta Island still in use and why has it not just become an extinct heritage practice? How beautiful it is to read about it in reports and studies, and how lovely its images appear online—yet how harsh it is to live inside these buildings as they are, without modern conveniences.

The lifestyle and daily tasks assigned to men and women on the island is key to understanding how these buildings are used, as frequent social visits, working in farms and being in outdoor spaces help ease the severity of the summer heat and winter cold that you can experience in these buildings. The island’s residents don’t stay in their rooms all day, as I did, being a newcomer from the city.

Another challenge of this architecture is its durability—it is constantly exposed to destruction and turns into ruins just a few years after being abandoned, unlike buildings made of other materials (stone, cement, or red brick). Regular maintenance is an essential part of life on the island, as homes are treated like living beings with their own needs, and residents do not complain about taking care of them. Interestingly, abandoned buildings played a crucial role in housing displaced people and returning islanders during the war. Due to the simplicity of construction techniques, the ruins were quickly restored to accommodate the large influx of people.

Building mud houses on Dagarta Island was never a matter of choice. The island’s isolation and the difficulty of transporting modern construction materials, along with limited space preventing the construction of brick kilns without causing health hazards, made mud-brick construction the only viable option. Of course, some Islanders can afford to transport these materials, but only very few. Only major projects funded by the government or private sources—such as the only primary school, the medical centre, and the two mosques (referred to as “Qibli” and “Bahri,” meaning south and north of the island)—were built using red bricks and finished with modern materials.

The economy of most island residents depends on seasonal agriculture, growing crops such as wheat, fava beans, and dates, while partially relying on financial support from their expatriate children. In recent years, fertilizers and pesticides have become essential to ensure successful harvests, as the nutrient-rich silt that once replenished the soil has significantly declined as a result of the construction of the Merowe Dam. Additionally, the selling price of crops for islanders is much lower compared to mainland residents, as farmers must bear the cost of transporting their produce across the river. These economic factors must be considered when asking why most houses are still built using traditional methods and why they lack modern cooling and heating systems to ease the hardships of extreme weather.

One positive government-provided service is the water network, which has connected pipes to every home. However, there is also a downside: before this network, women would go to the Nile to fetch water, turning it into a social activity. All elderly women on the island know how to swim. They did not stay indoors suffering from the intense heat during the day. Thus when we look at any solution offered for an age-old problem, we realize it often brings unintended consequences.

What Does the House Consist Of?

A typical mud house consists of rooms, barandat, verandas, a kitchen, and a storage area. Additional structures outside the main enclosure include an outdoor kitchen for making traditional bread if space inside the house is limited, a latrine, a pigeon tower, a rakuba (a shaded sitting area for men with chairs and beds for receiving guests), an outdoor traditional clay water dispenser mazyara, and a platform for storing produce rasa and grain silo gosayba.

Regarding sanitation, there is no sewage network due to the island's small size, nor are there sewage suction tanks, as there are no motorized vehicles on the island—except for one plow owned collectively by the island’s farmers. The common solution is pit latrines, it’s a system that consists of digging a pit behind the bathroom connected with PVC drainage pipes and a ventilation outlet. As it’s a dry system, water usage is minimized to slow the filling of the well. Water from washing drains into an external pit, which is later emptied. When a washroom pit fills up, the washroom is abandoned, and a new one is built with a new pit. If space is limited, the washroom may be built outside the house. Dishwashing water is collected in a basin and bucket, then poured into the street, directed to an alley, or drained onto an empty plot of land.

Building Materials and Construction